Meeting the Moment

Family Planning and Gender Equality

![progress2023-2048x1328[1]](https://www.fp2030.org/app/uploads/2024/12/progress2023-2048x13281-1.jpg)

Table of Contents

This report comes at a critical time in our movement. We’re at the intersection of several crises.

Measurement Overview

Voluntary, rights-based family planning is essential for progress on gender equality.

Global Trends

After a decade of progress during the FP2020 partnership and resilience in the face of the global COVID-19 pandemic, the global family planning movement faces new challenges.

Regional Profiles

This year, with commitments in hand from every region with an FP2030 hub — Asia and Pacific; East and Southern Africa; North, West, and Central Africa; and Latin America and the Caribbean — we expand our scope to include all four regions.

Foreword

Globally, 800 women are dying every day in childbirth. 218 million women in low- and middle- income countries have an unmet need for modern contraception — meaning they want to avoid a pregnancy but are not using a modern method.

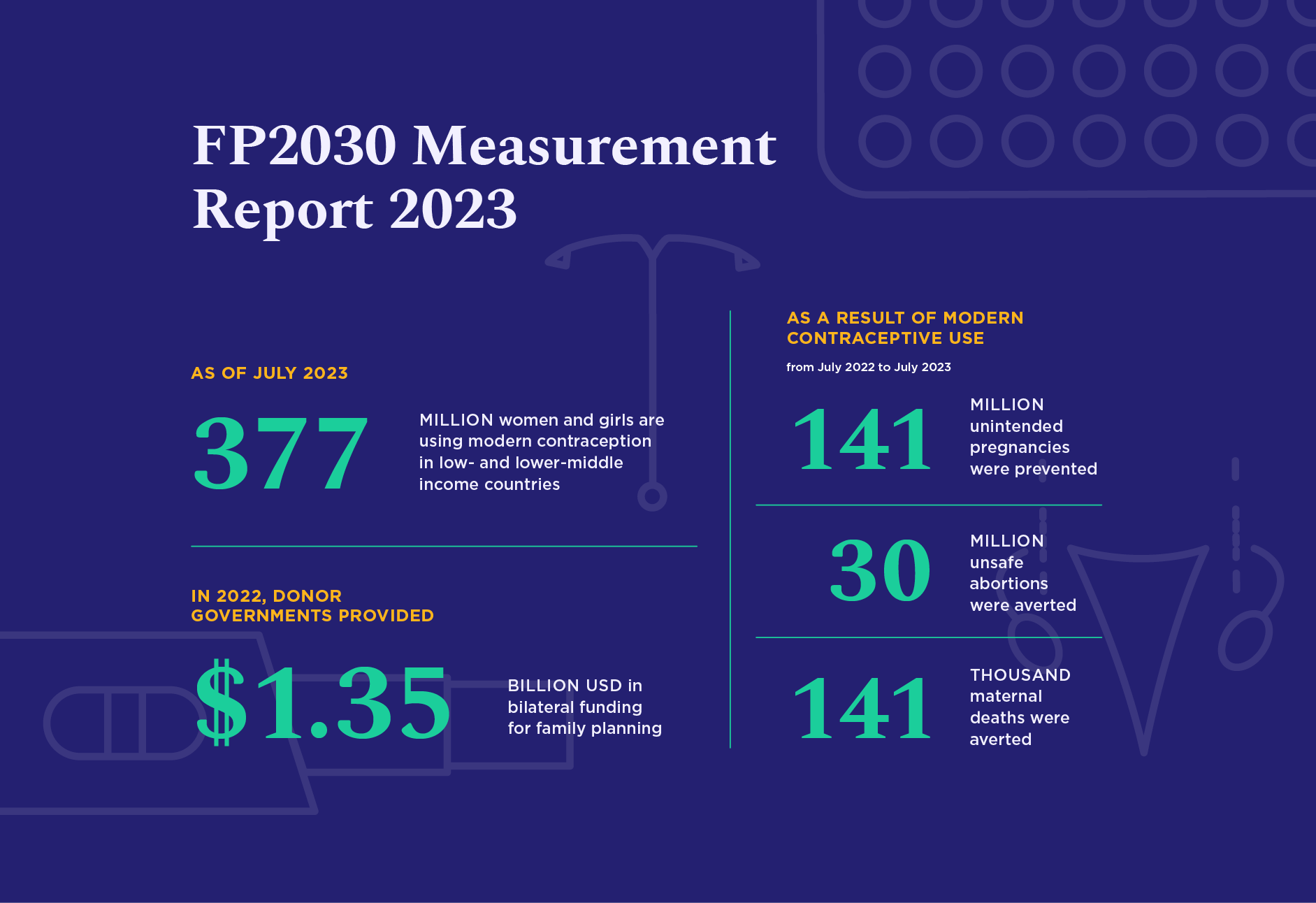

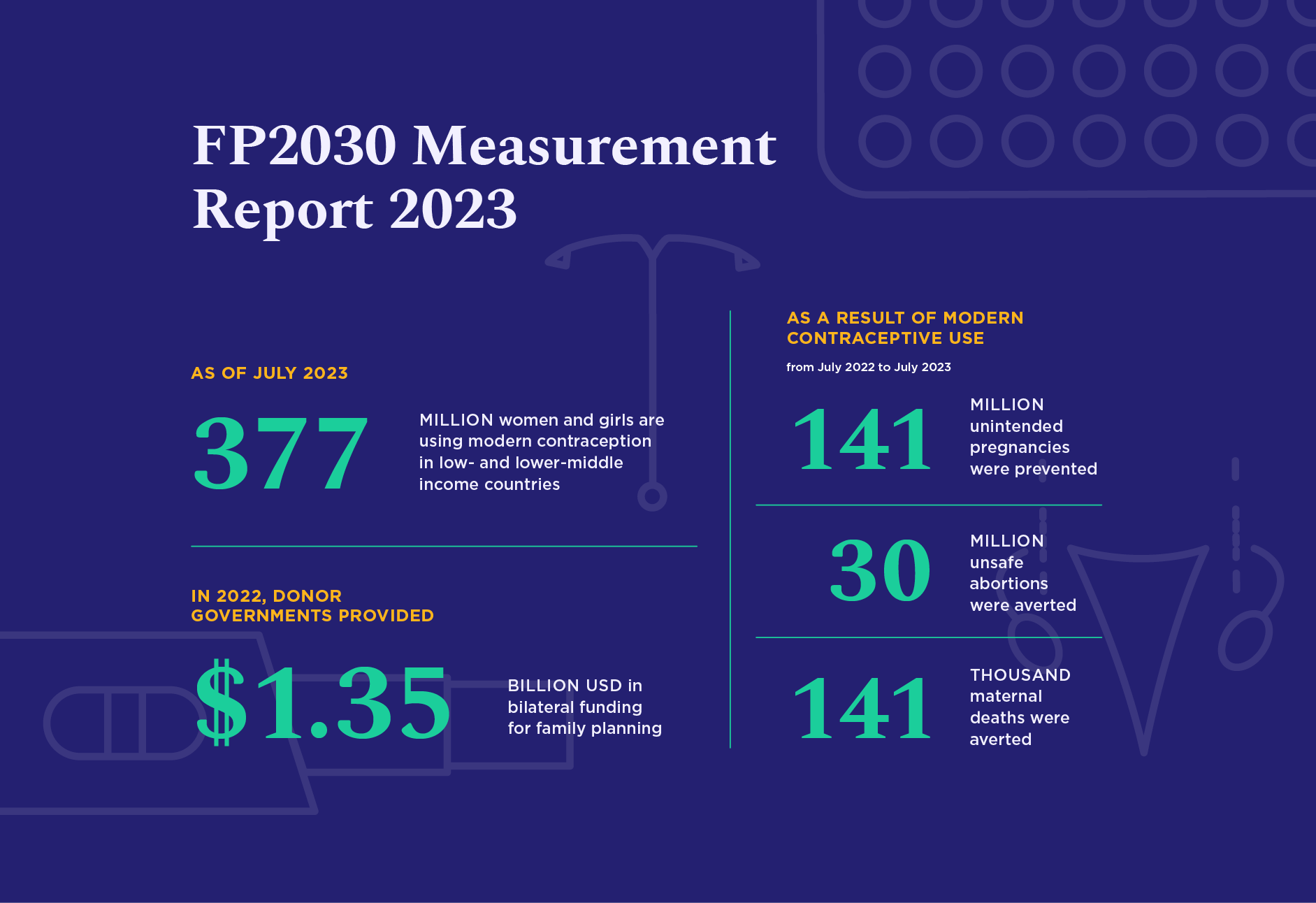

Measurement Overview

Until women are able to decide for themselves what happens to their own bodies, gender equality will remain an unreachable dream.

Access to contraception is the critical factor that unlocks a world of possibilities for women and girls: finishing school, pursuing a career, planning for and starting healthy families, and participating fully as equal members of society. Voluntary, rights-based family planning is essential for progress on gender equality.

Global Trends

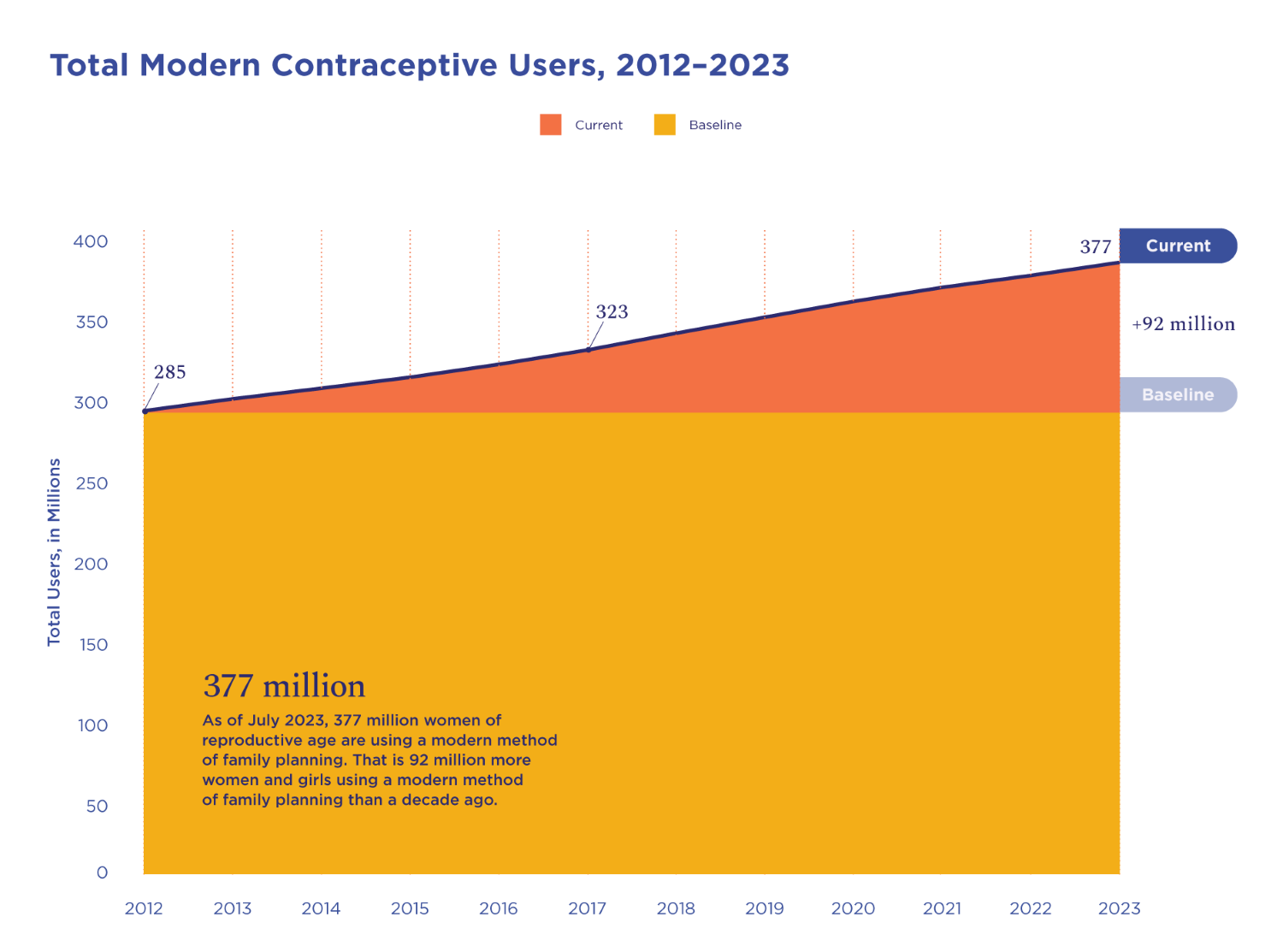

Global Trends finds the family planning movement at a pivotal moment, with progress in contraceptive use juxtaposed against diminishing international aid and shifting political priorities.

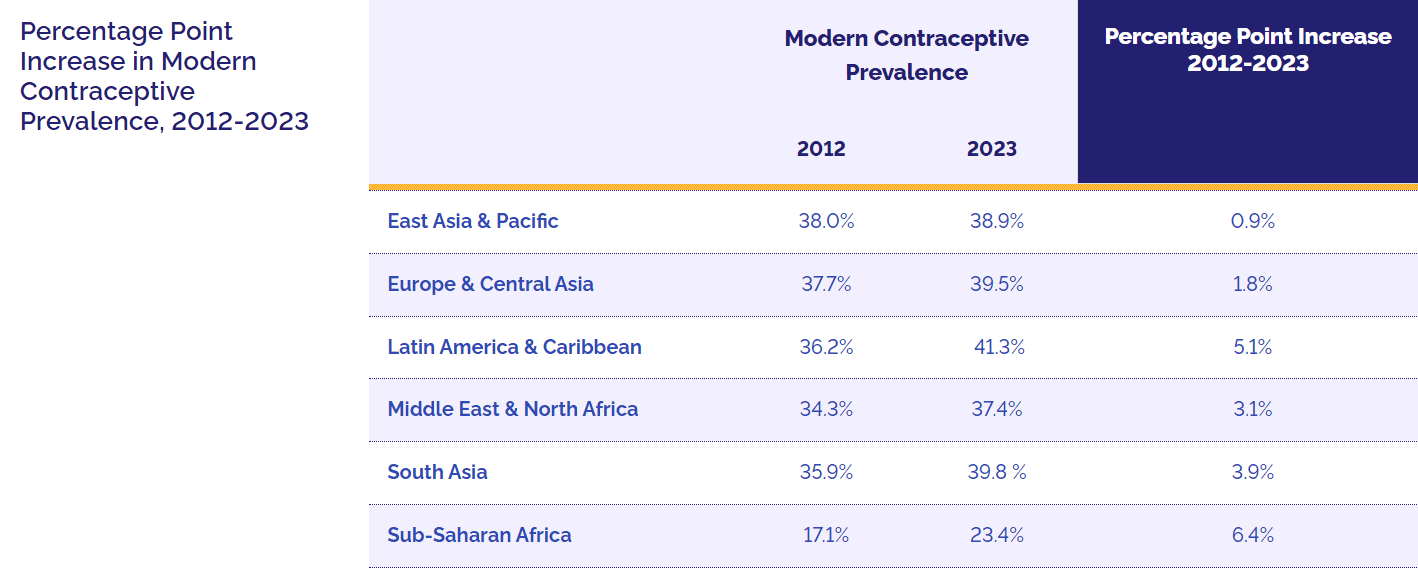

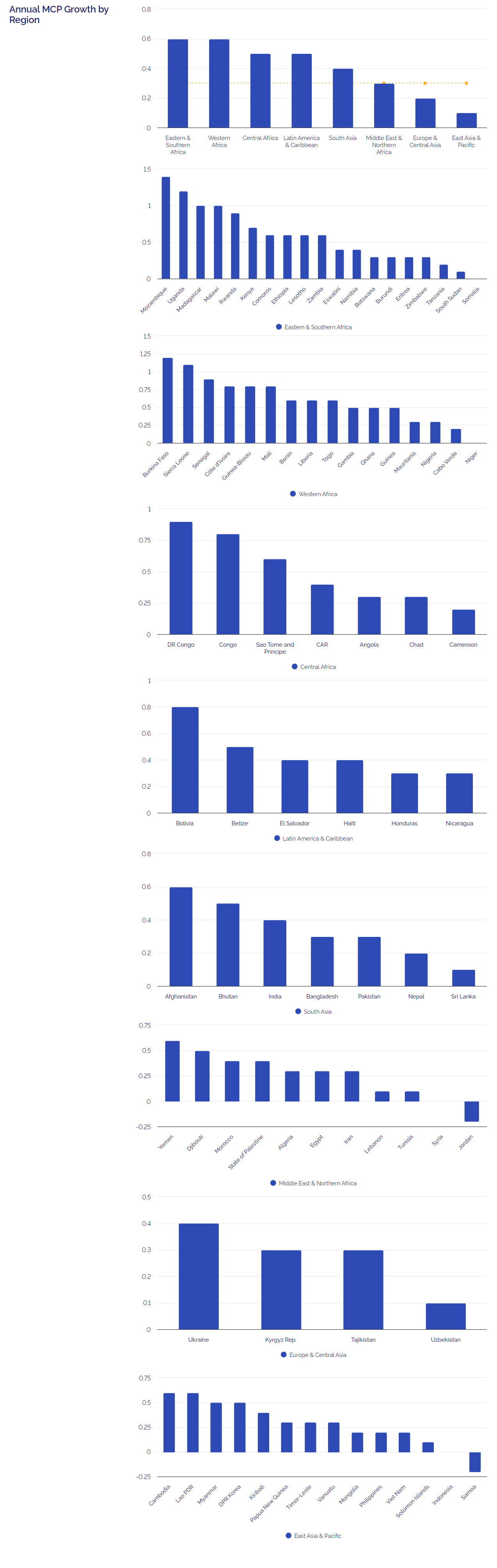

The number of women using modern contraception has grown by 92 million since the outset of this partnership in 2012, and modern contraceptive prevalence has increased to 35.2%. Countries with the lowest levels of contraceptive use a dozen years ago are now in the midst of a family planning boom, other countries have successfully reinvigorated aging programs, and highly effective, long-acting implants have become the method of choice across much of Africa.

Regional Profiles

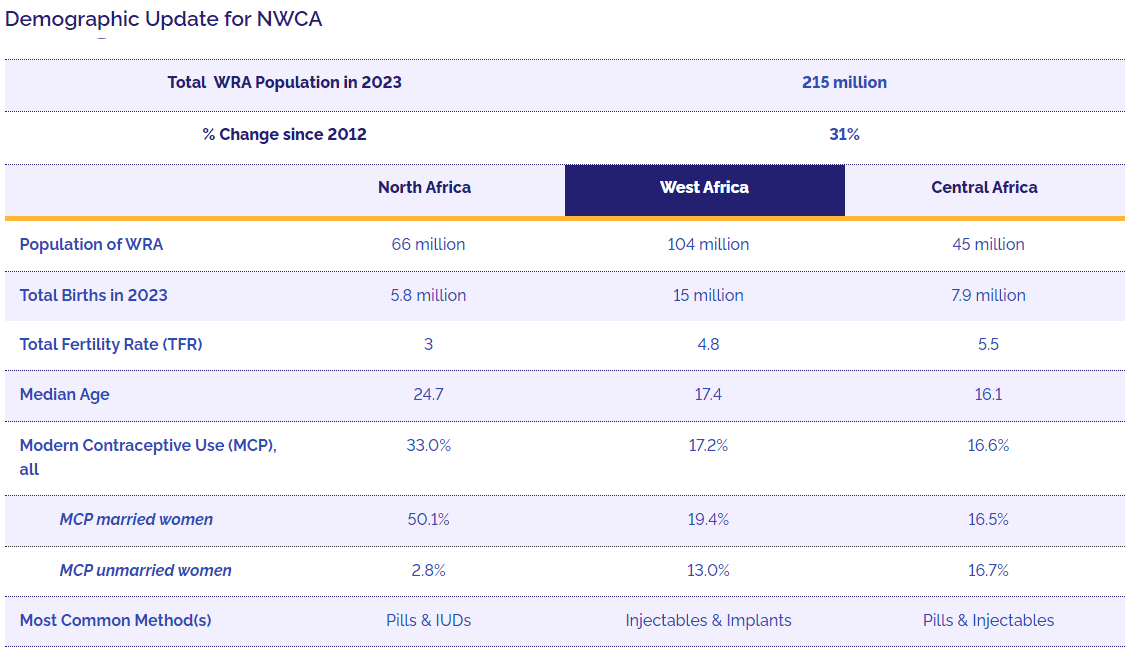

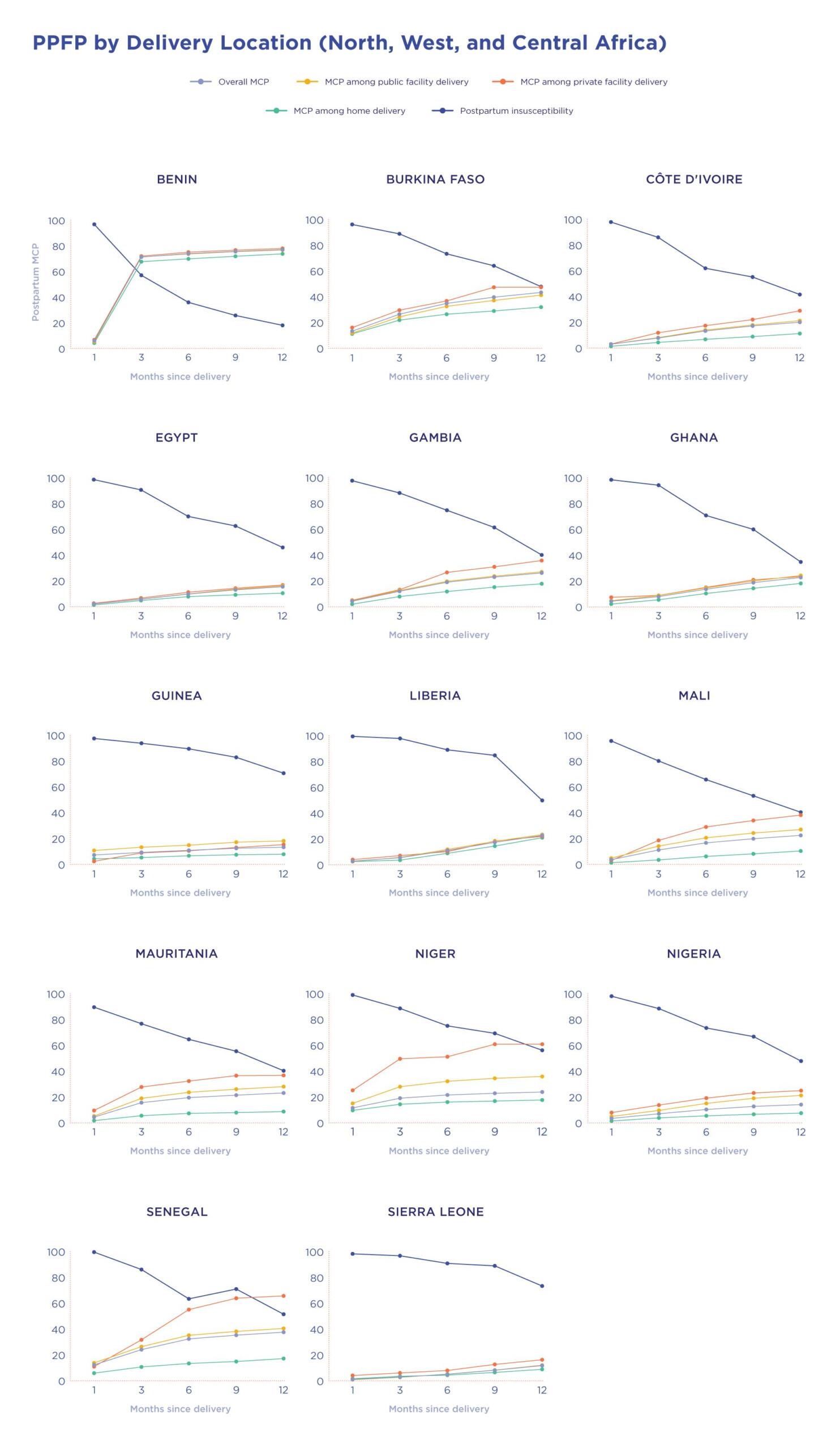

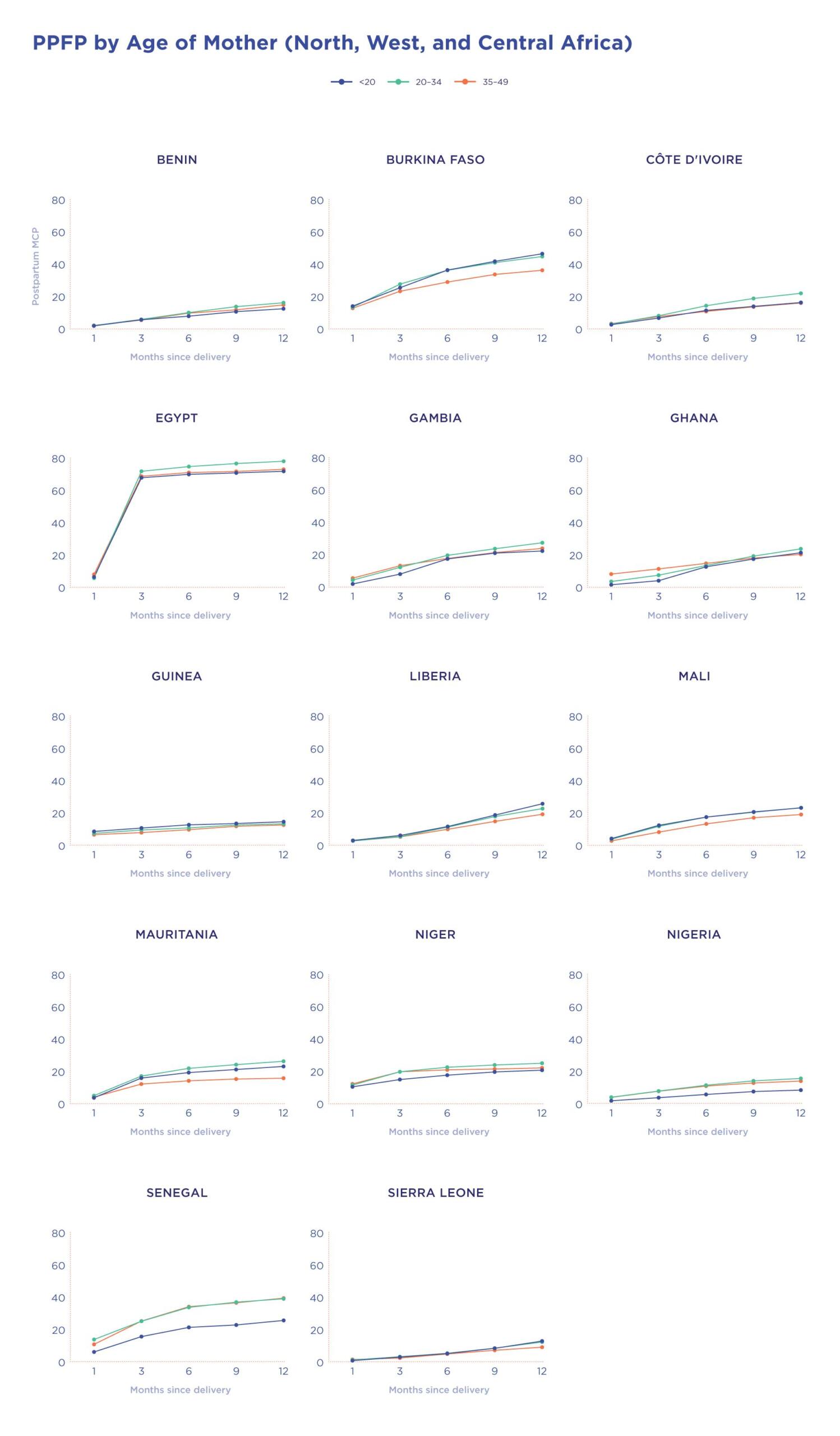

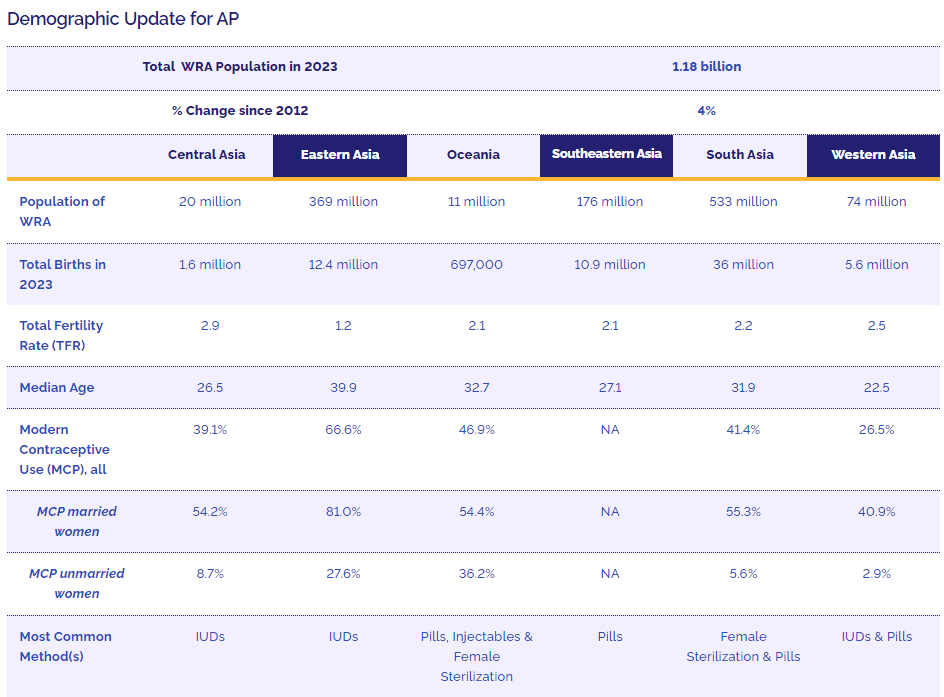

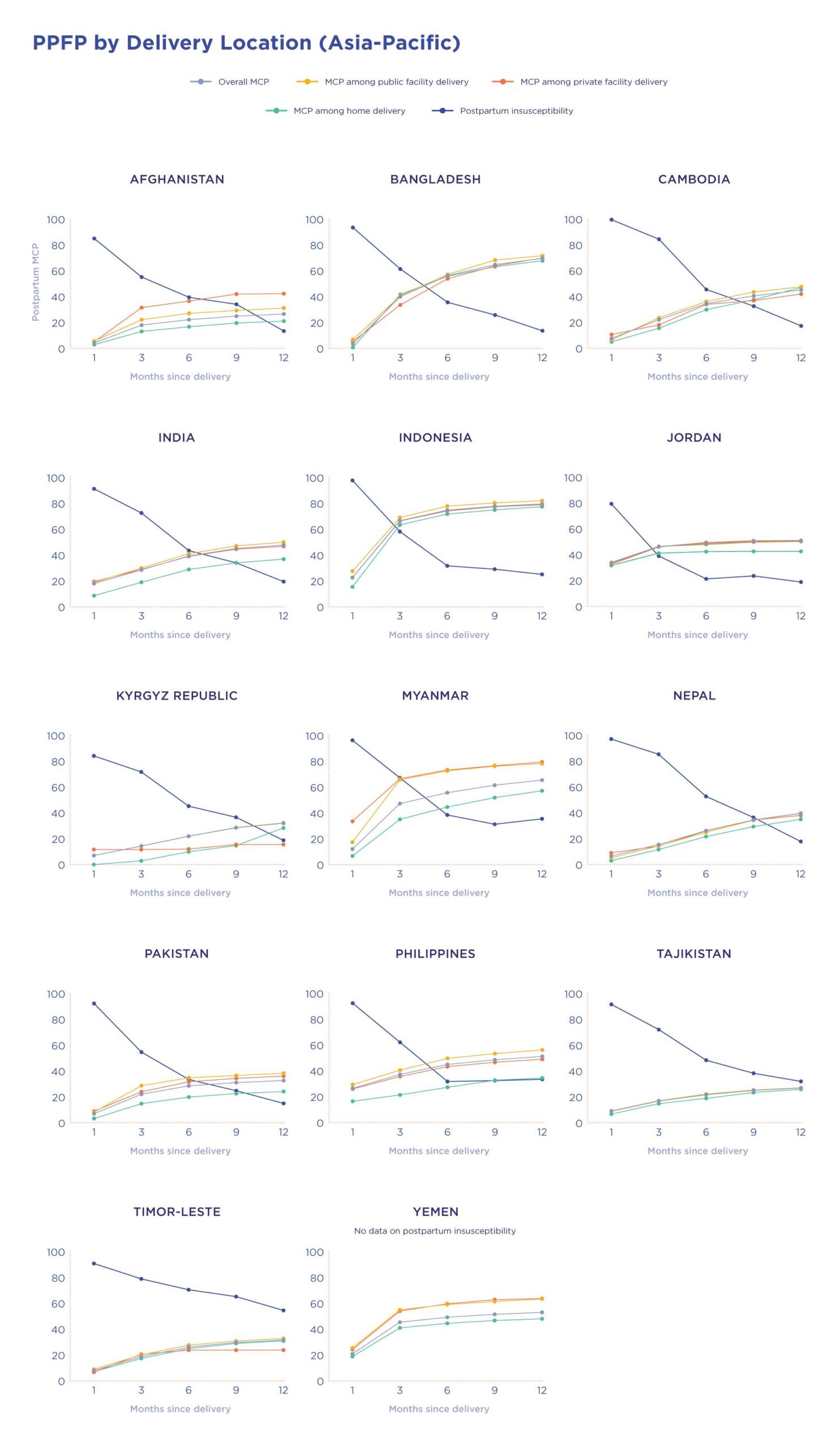

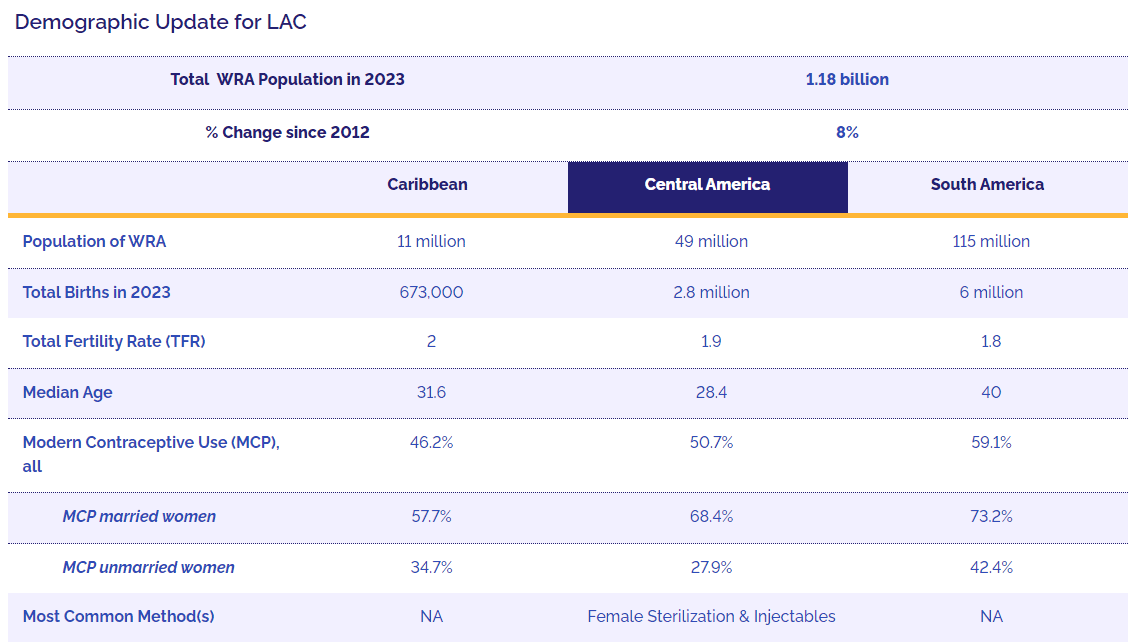

In last year’s report we opted for a narrow approach to the Regional Profiles section, focusing only on Sub-Saharan Africa and the 15 countries in the region that had finalized their FP2030 commitments by August 2022. This year, with commitments in hand from every region with an FP2030 hub — Asia and Pacific (AP); East and Southern Africa (ESA); North, West, and Central Africa (NWCA); and Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) — we expand our scope to include all four regions.

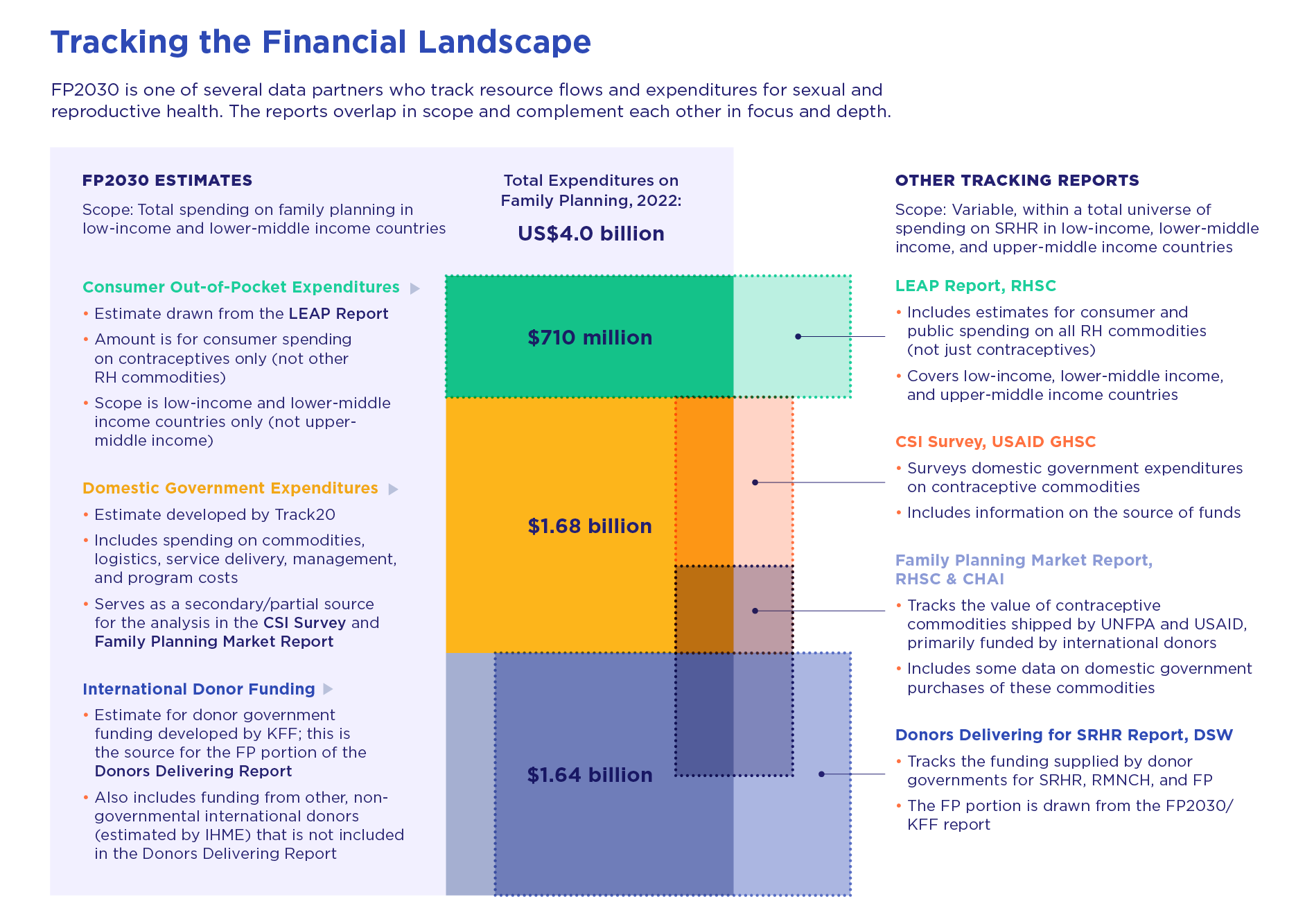

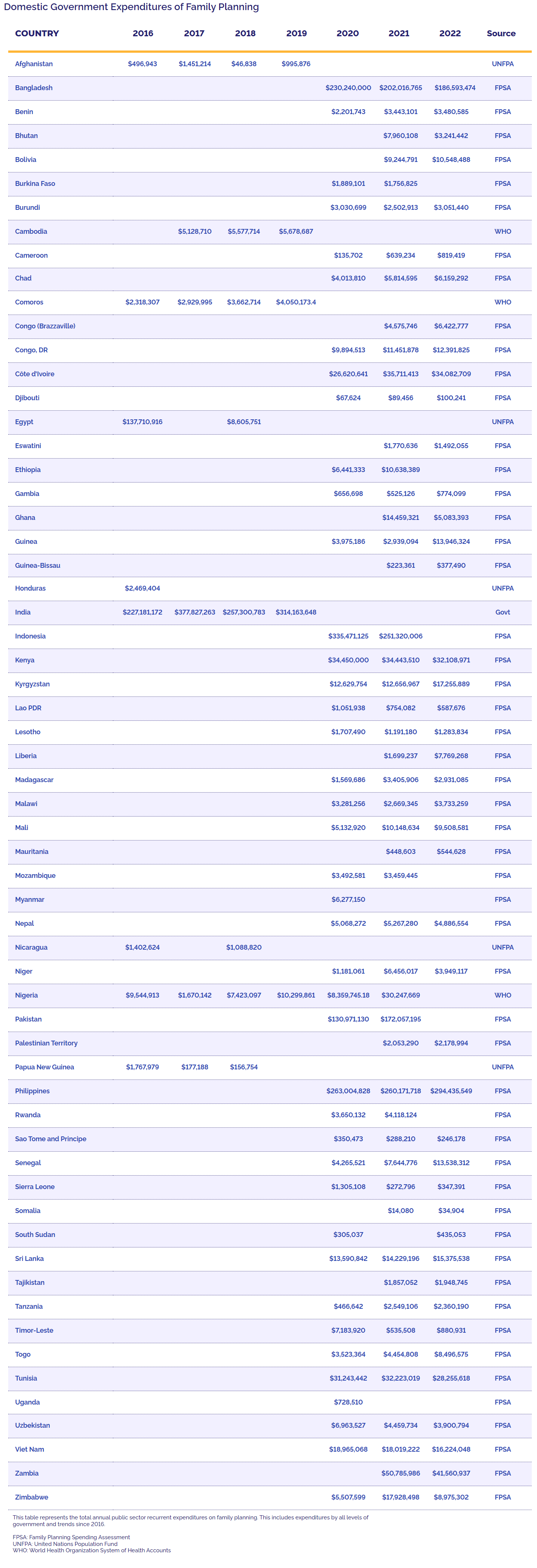

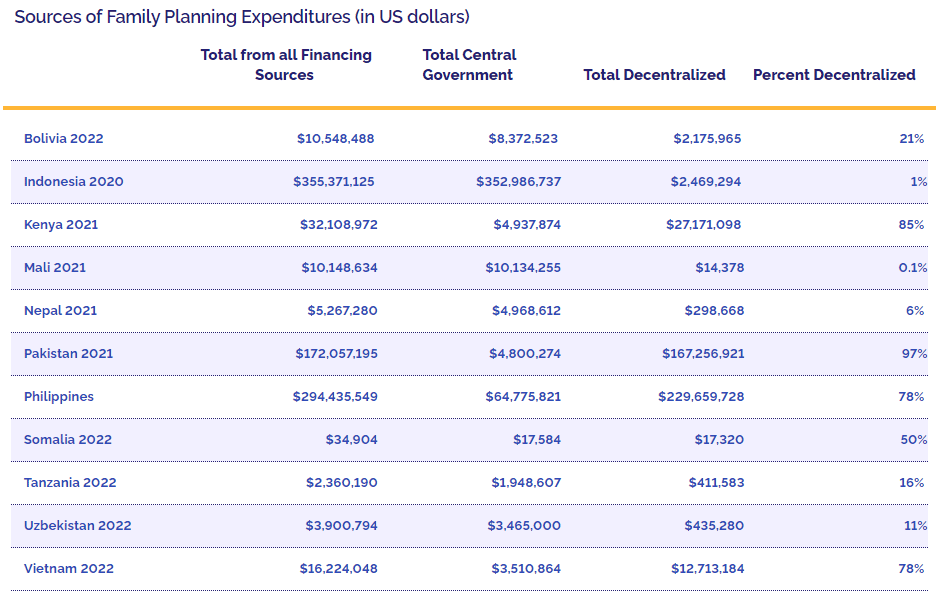

Finance

Global funding for family planning is a stool with three legs: domestic government expenditures, international donor contributions, and consumer spending.

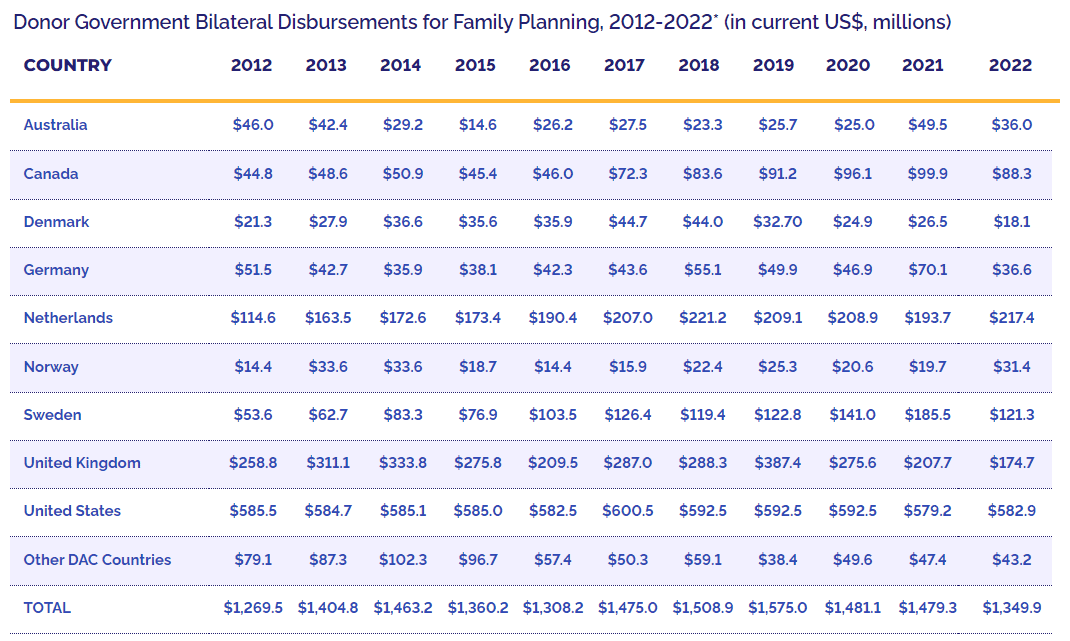

Donor Government Funding for Family Planning In 2022: KFF Summary Analysis

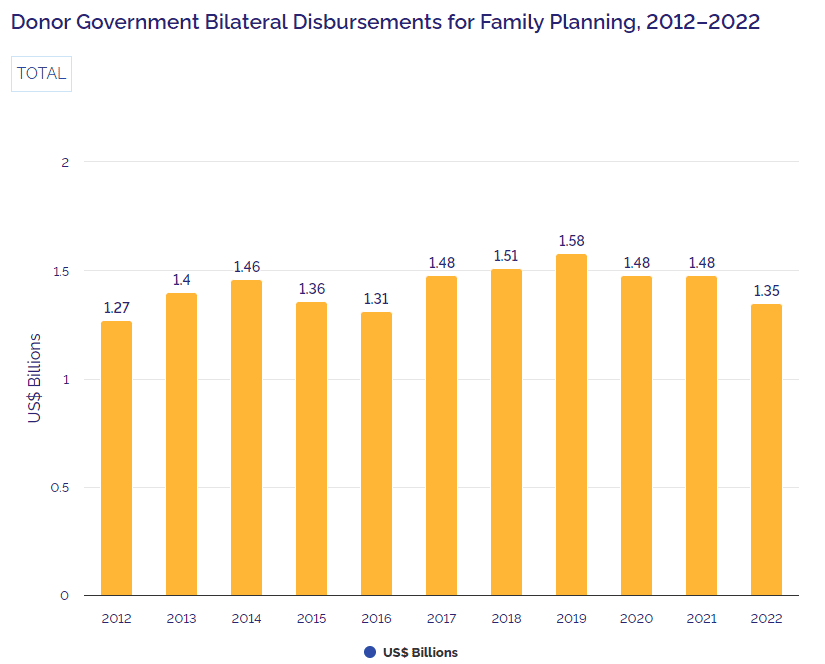

Donor government total disbursements for family planning

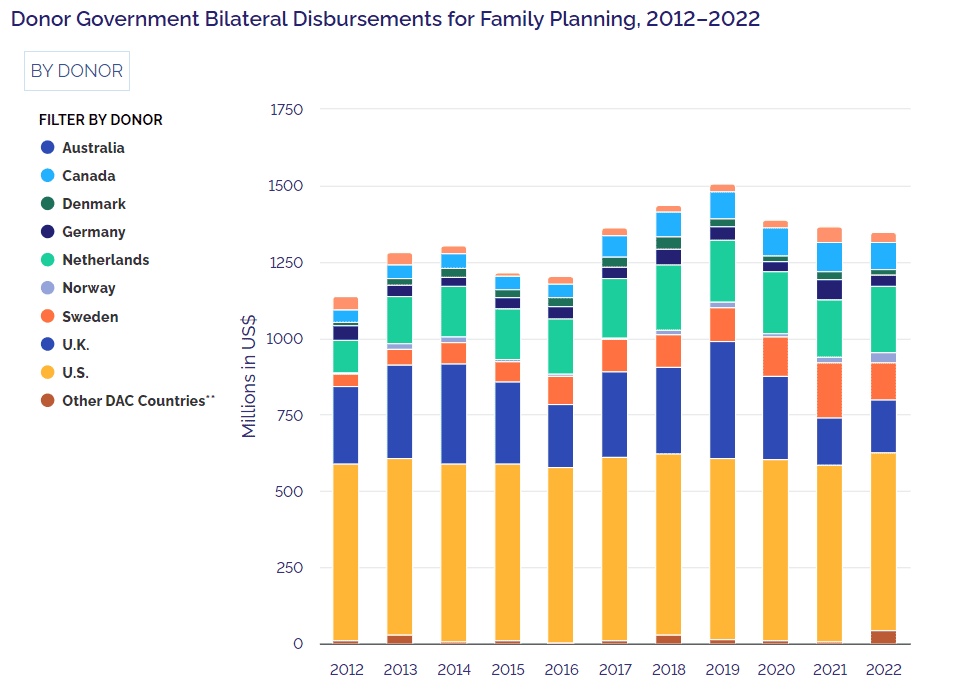

Individual donor government disbursements

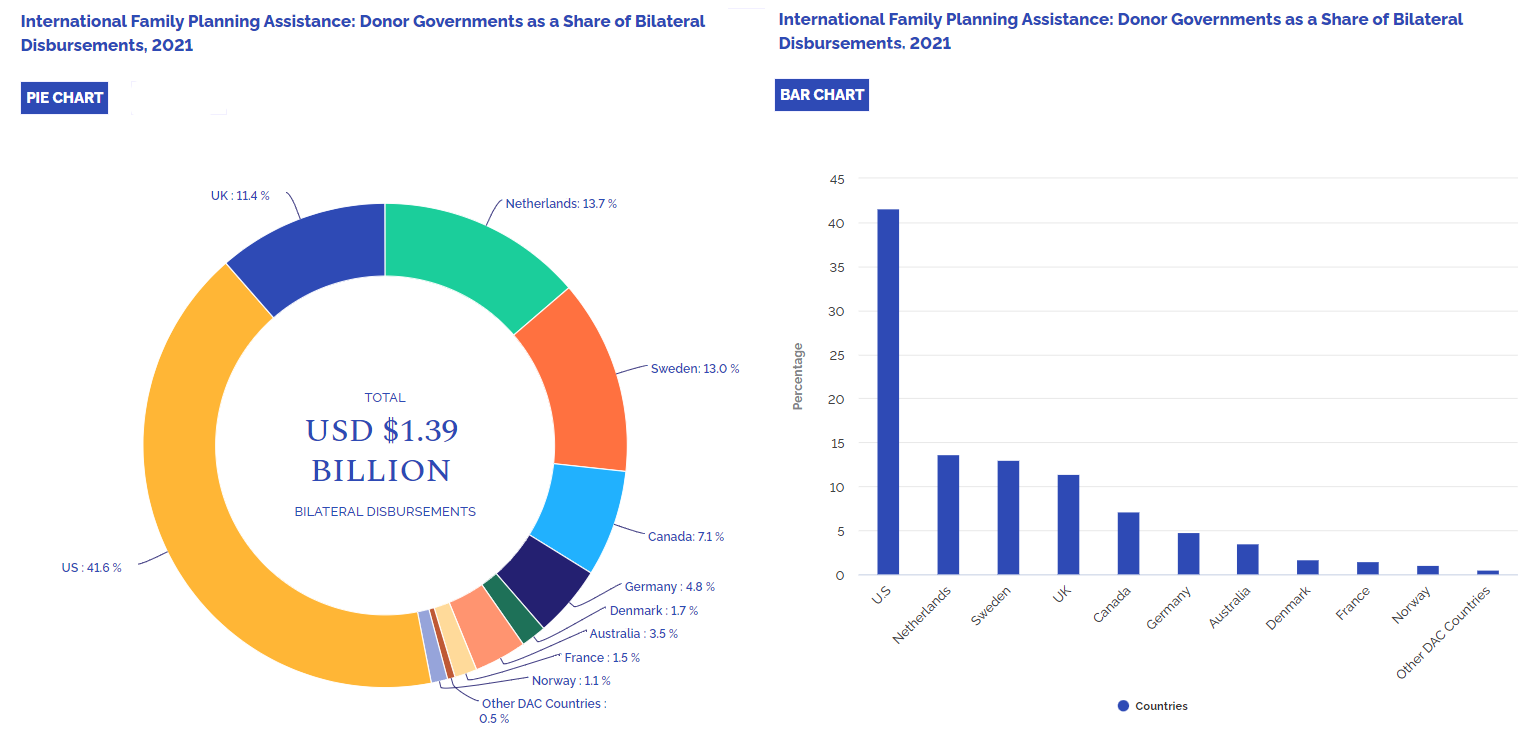

Donor governments as a share of total disbursements

Other International Donors

Resources

The FP2030 Measurement Framework includes more than 20 indicators, such as Modern Contraceptive Prevalence, Unmet Need, Demand Satisfied, and Method Mix.

Interactive & Country Data Resources

The data includes estimates from 2012-2023 for all FP2030 indicators in the measurement framework for 84 low and low-middle income countries as well as upper-middle income countries that have made a commitment to FP2030. The new file has updated information for all the FP2030 indicators and includes three new countries – Botswana, Jordan, and Namibia. Some indicators are annually modeled while others are based on the most recent surveys. Additionally, some indicators are disaggregated by wealth quintile. Read the FP2030 Measurement Framework for more details on the definition, calculation, disaggregation, and source for each indicator.

Estimate tables

This file contains estimates for all the FP2030 indicators in the measurement framework and is reported for the years 2012-2023.

AY data file

A supplemental data file on the adolescent and youth sexual and reproductive health (AYSRH) indicators.

Data dashboard

An interactive data dashboard highlights key indicators from the measurement framework and data on family planning financing.

Track20 Opportunity Briefs

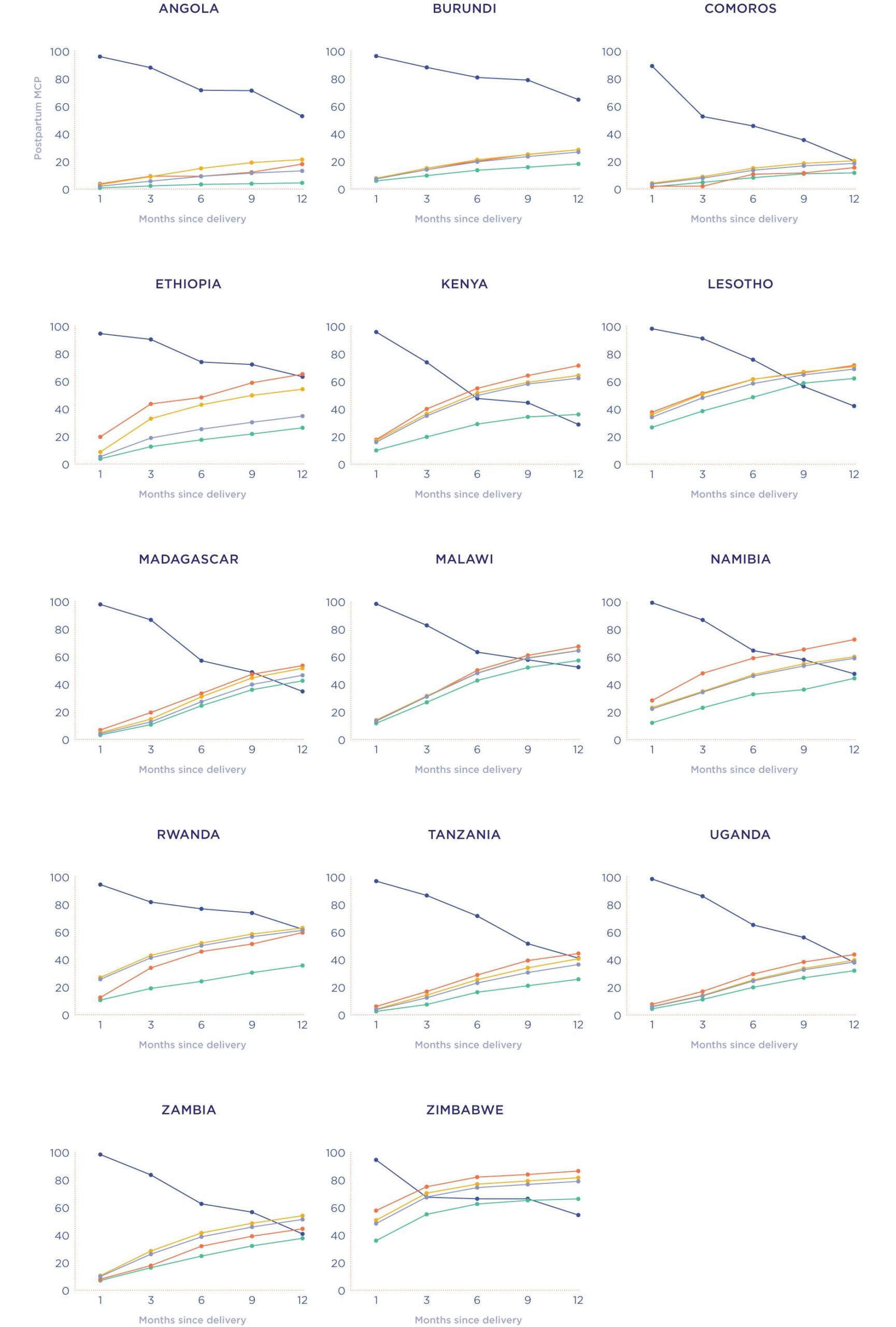

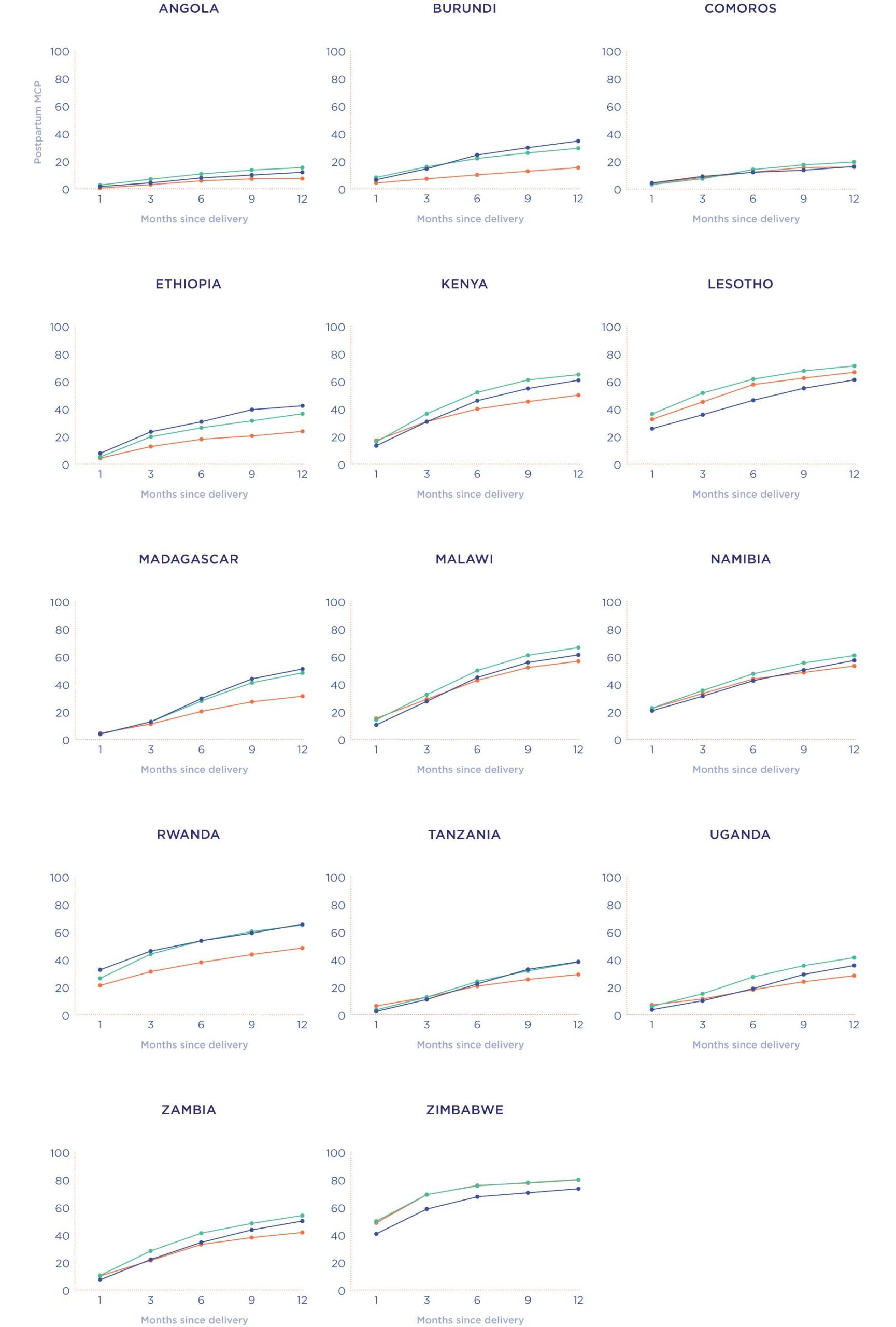

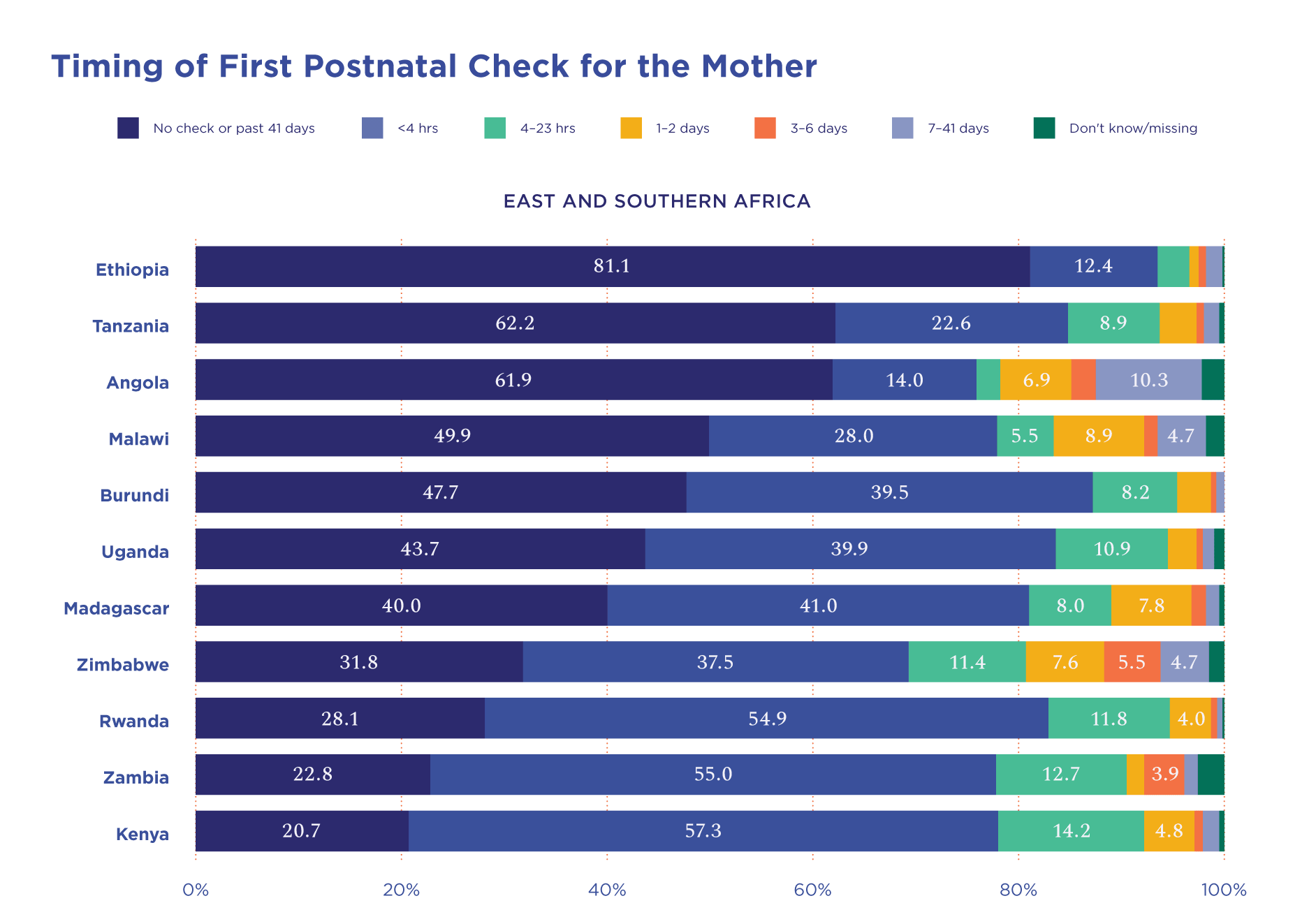

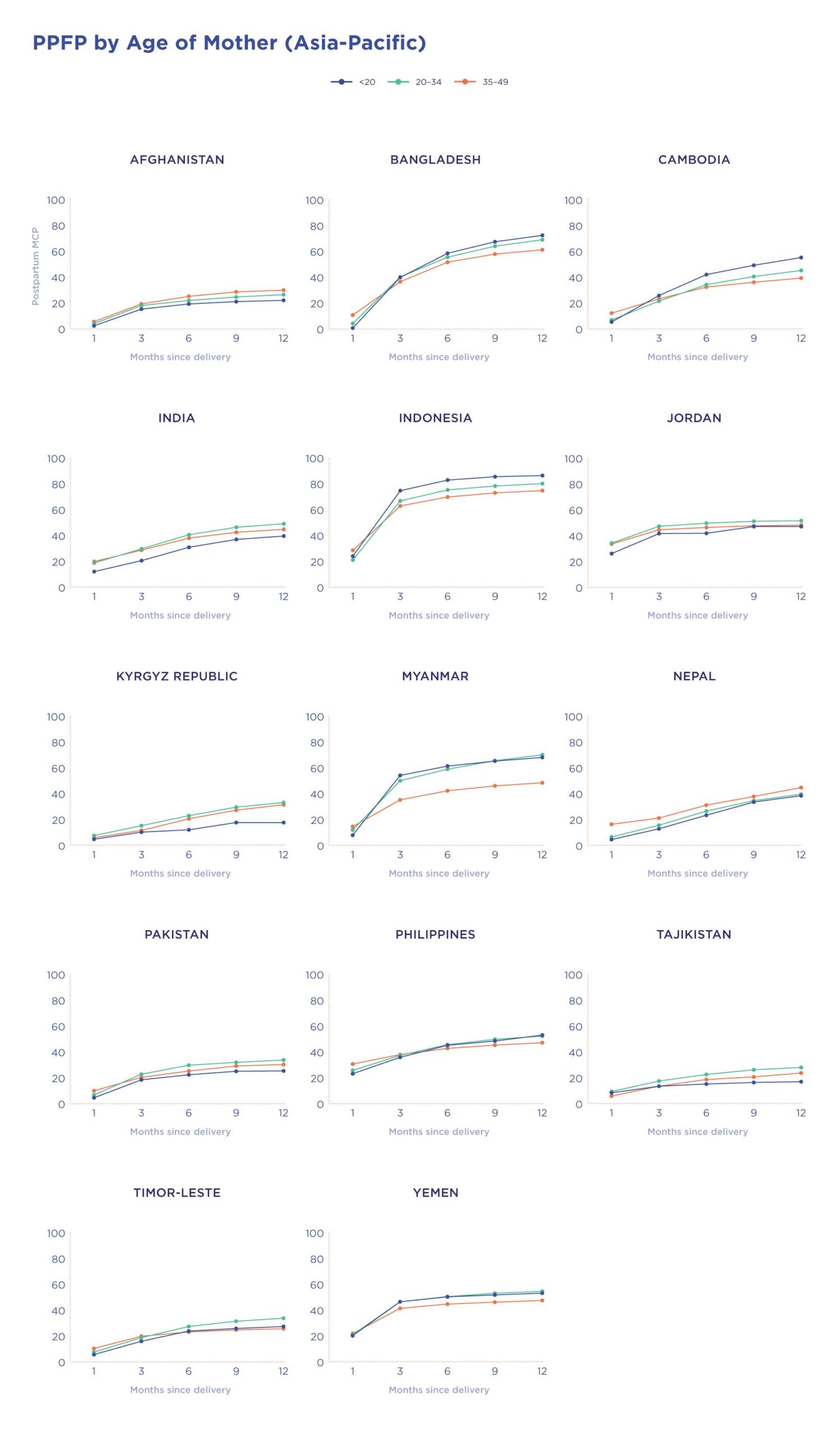

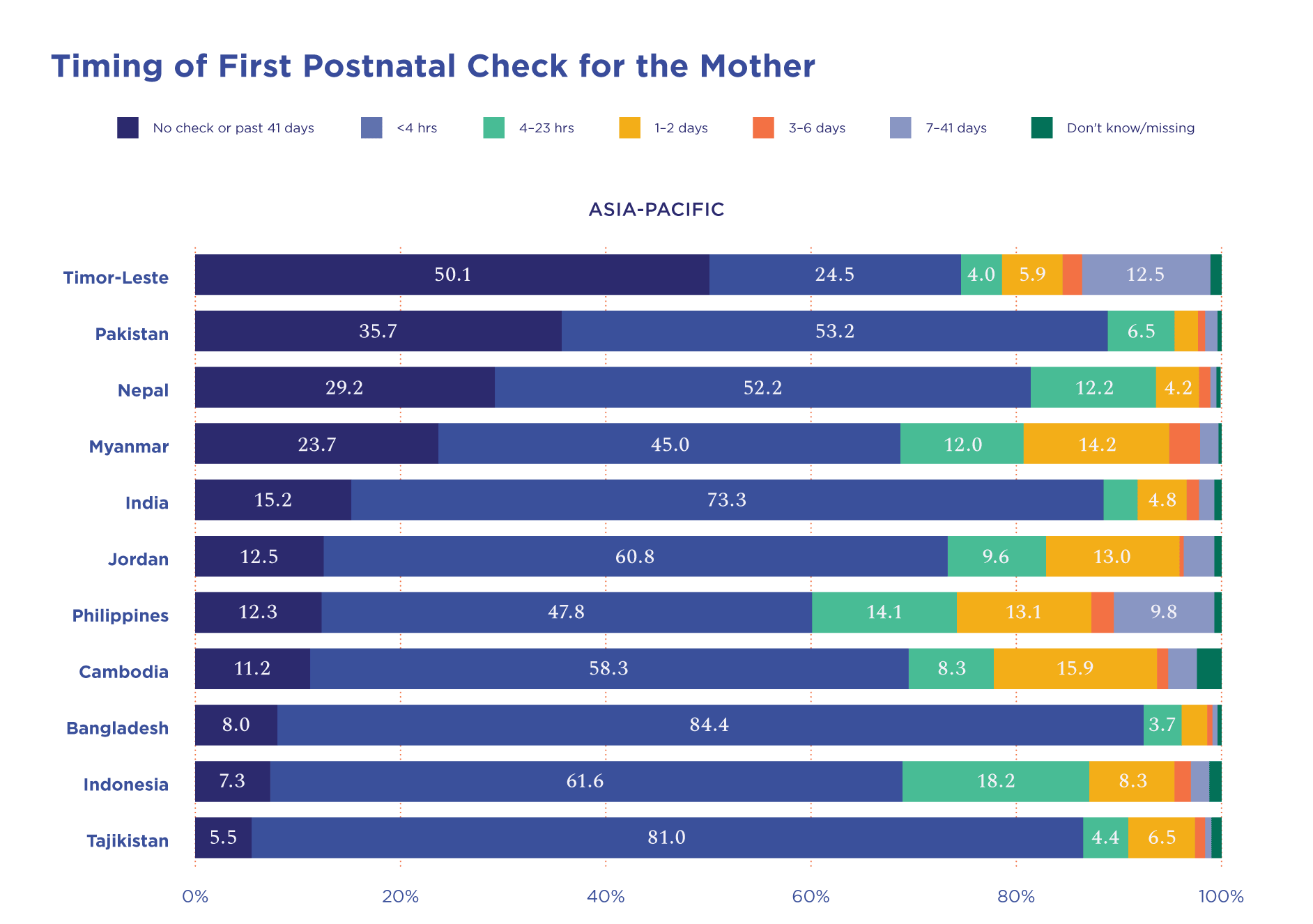

The “Track20 Country Opportunity Briefs” bring together a wide range of data sources to allow for exploration of these key areas of Overall Growth, PPFP, and Youth Access.

Track20 country FP indicator summaries

The Track20 FP indicator summaries and fact sheets highlight data for all indicators for all low income and lower-middle income countries.

Uncertainty Estimates 2023 Report

A supplemental data file to report uncertainty ranges for survey-based and modeled estimates to lend credibility to our methods.